Μελέτη - Περιοδικό για Μαθητές

Σάββατο 31 Μαρτίου 2018

Free online word cloud generator and tag cloud creator - WordClouds.com

Free online word cloud generator and tag cloud creator - WordClouds.com: Wordclouds.com is a free online word cloud generator and tag cloud generator, similar to Wordle. Create your own word clouds and tag clouds. Paste text or upload documents and select shape, colors and font to create your own word cloud. Wordclouds.com can also generate clickable word clouds with links (image map). Save or share the resulting image.

Τετάρτη 4 Ιανουαρίου 2017

τεστ svg

Αντιγράφεις από τον editor http://www.w3schools.com/graphics/tryit.asp?filename=trysvg_myfirst

τον κώδικα στο Html αρχείο και έχεις την εικόνα svg.

Accessibility Features of SVG

Accessibility Features of SVG

W3C Note 7 August

Copyright © 1999-2000 W3C® (MIT, INRIA,

Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C

liability,

trademark, document

use and software

licensing rules apply.

features to make graphics on the Web more accessible than is currently

possible, to a wider group of users. Users who benefit include users with low

vision, color blind or blind users, and users of assistive technologies. A

number of these SVG features can also increase usability of content for many

users without disabilities, such as users of personal digital assistants,

mobile phones or other non-traditional Web access devices.

Accessibility requires that the features offered by SVG are correctly used

and supported. This Note describes the SVG features that support accessibility

and illustrates their use with examples.

Publication of this Note by W3C indicates no endorsement by the W3C

Team or any W3C Members. The Note is based on the

SVG Candidate Recommendation [SVG].

This Note is made available at the same time as the SVG

Candidate Recommendation in order to provide

information on potential implementation considerations.

This version of the Note has received some review but not yet endorsement

from the SVG Working Group and the Protocols and Formats Working Group. These

groups, together with the Education and Outreach Working Group, the WAI

Interest Group, and others are invited to review this document,

in particular, during the SVG Candidate Recommendation period.

The authors plan to publish an updated version of this Note in any of the

following circumstances:

mailing list w3c-wai-eo@w3.org, which

is archived

publicly at http://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/w3c-wai-eo/. This document

has been produced as part of the WAI

Technical Activity. A list of current W3C technical reports

and publications, including Working Drafts and Notes, can be found at

http://www.w3.org/TR.

information on the Web. In many cases, images have an important role in

conveying, clarifying, and simplifying information. In this way, multimedia

itself benefits accessibility. However the information presented in images

must be accessible to all users, including users with non-visual devices.

Furthermore, in order to have full access to the Web, it is important that

authors with disabilities can create Web content, including images as part of

that content.

The working context of people with (or without) disabilities can vary

enormously. Many users or authors:

and authors including many people who do not have a disability but who have

similar needs. For example, someone may be working in an eyes-busy environment

and thus may require an audio equivalent for information they cannot view.

Users of small mobile devices (with small screens, no keyboard, and no mouse)

have similar functional needs to users with certain disabilities. For some

further information on how people with disabilities use the Web, refer to "How

People with Disabilities Use the Web" [USENOTE].

Language (XML) application for producing Web graphics. SVG

provides many accessibility benefits to disabled users, some originating from

the vector graphics model, some inherited because SVG is built on top of XML,

and some in the design of SVG itself, for example, SVG-specific elements for

alternative equivalents.

SVG images are scalable - they can be zoomed and resized by the reader as

needed. Scaling can help users with low vision and users of some assistive

technologies (e.g., tactile graphic devices, which typically have a very low

resolution).

The following example illustrates the scalability of a vector graphics

image. The first row shows a small PNG and a corresponding

SVG image, which look the same. The second row shows an enlargement of both.

The enlarged PNG version of the image has suffered a significant loss of

quality, while the enlarged SVG version looks smooth and shows more details

than before. Scalable graphics can help users with low vision make sense of an

image at a size that best suits their needs.

GIF or PNG images) accessible on the Web is to

provide a text equivalent that may be rendered with or without the image.

Often, this text equivalent is the only information available for non-visual

rendering, as the raster image is stored as a matrix of colored dots,

generally with no structural information. Structural information can be added

to any image as metadata, but managing it separately from the visible image is

tedious, making it less likely that authors will create and use it with

careful attention. SVG's

vector-graphics format stores structural information about graphical shapes as

an integral part of the image. As we discuss below, this information can be

used by assistive technologies to increase accessibility, especially when this

structural information is complemented by alternative equivalents and

metadata.

to help them understand the image. In particular, SVG authors to include a

text description for each logical component of an image, and a text title to

explain the component's role in the image as a whole. Text is considered very

accessible to users with a range of disabilities (e.g., some vision

impairments and some cognitive disabilities) since it may be rendered on

screen, as speech, or as Braille using readily available assistive technology.

encoded as plain text. Authors can create and edit it with a text-processor or

XML authoring tool (there are other properties of SVG that make this easier

than it might seem at first). A number of popular Web design tools are in fact

enhanced text-editing applications, and for users with certain types of

disabilities, these are much easier to use. Naturally, it is also possible to

use graphic SVG authoring tools that require very little reading and writing,

which helps people with other types of disabilities.

Plain text encoding also means that people may use relatively simple,

text-based XML user agents to render SVG as text, braille, or audio. This can

help users with visual impairments, and can be used to supplement graphical

rendering.

accessibility. Authors may use CSS or XSL style sheets to control the

rendering of SVG images, a feature common to all markup languages written in

XML. Users who might otherwise be unable to access content can define

stylesheets to control the rendering of SVG images, meeting their needs

without losing additional author-supplied style.

to provide specific graphic effects for controlling how images are rendered.

These style features can help authors to create content that can be easily

adapted to the needs of users with low vision, color deficiencies, or users

with assistive technologies. Features such as masking, filters, and the

ability to define highly sophisticated fonts are all available in SVG.

through the Document Object Model (DOM). The DOM interface

can enable the use of many assistive

technologies with SVG images. SVG allows access to both stylesheet and XML

content as it uses DOM version 2 (DOM2) [DOM2].

and may also include markup from other XML languages. Mixing markup language

can increase accessibility because authors may use the markup language most

suited to each part of a document (refer to the Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines 1.0 [WCAG10], Guideline 3). For instance, a

MathML document could use SVG for both laying out equations and drawing graphs

of those equations. In examples below, we show how to describe SVG components

and their relationships by embedding RDF metadata and SMIL markup in the

SVG.

Sections 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 we discuss the accessibility features of SVG

(including the use of stylesheets). Section 7 explains the accessibility

benefits that originate from XML.

This document makes extensive reference to the accessibility requirements

specified in the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 Recommendation

(ATAG10) [ATAG10], the Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 Recommendation (WCAG10) [WCAG10], and the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines

Working Draft (UAAG10) [UAAG10]. It

also makes extensive reference to Cascading Style Sheets Level 2

(CSS2) [CSS2]. A reader who has a basic

knowledge of HTML or XML and of CSS (level one or two) should be able to

understand enough of the markup to make sense of the examples. Even without

that knowledge, it is worth reading the examples to see how they work - as

well as illustrating accessible design in many cases they demonstrate good

general design practices.

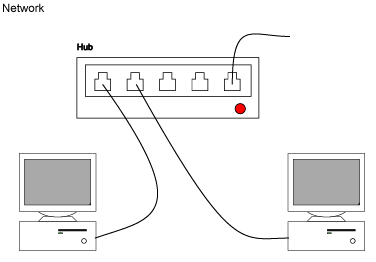

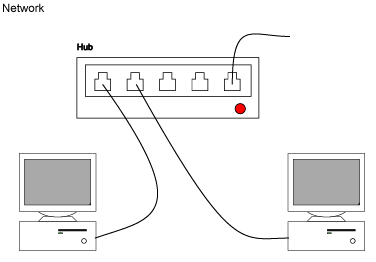

To illustrate how to create accessible SVG graphics, we design an SVG

diagram of a computer network, built up from example to example. Examples use

strong emphasis to highlight changes from example to example,

or important features of an example.

primary ways authors can make their documents accessible to people with

disabilities. The alternative content fulfills essentially the same function

or purpose for users with disabilities as the primary content does for users

without any disability. Text equivalents are always required for graphic

information (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoint 1.1, and

Guideline 1 in general). In SVG, providing a hierarchy of text equivalents can

also convey the hierarchical structure of the graphic components. This Note

describes a number of ways to include and use equivalent alternatives.

include the following elements in any SVG container or graphics element:

and a description for an image of a computer network. The graphic components

that can actually be drawn will be added to the image in later sections.

each of which may have a title and a description. The combination of the

hierarchy and alternative equivalents can help a user who cannot see to create

a rough mental model of an image. SVG authors should therefore build the

hierarchy so that it reflects the components of the object illustrated by the

image. Some guidance for using structure can be found in WCAG10 (refer to [WCAG10], Guidelines 3 and 12).

The component hierarchy with alternative equivalents can be used in

different ways by different user agents. For instance, a simple non-visual

user agent can provide access to the component hierarchy and allow the user to

navigate up and down or at a certain level of the structure, giving the

equivalent description of each encountered component (refer to UAAG10 [UAAG10], Checkpoints 7.6 and 7.7 and Guidelines 7 and 8). A

standard XML browser, which does not render SVG as graphics, may also do this.

A multimedia-capable user agent might name each component that has focus

through speech output, much as some Web browsers render alternative text for

images as tooltips.

The following example (2.2) extends the network image component introduced

in example 2.1 by introducing six subcomponents:

an

One simple way a user agent could render the image in Example 2.2 is to

show the alternative equivalents as text, as in the next figure (2.3). Example 4.2 in Section 4 shows how to

attach CSS2 [CSS2] style information to the

without definitions for these elements, a user agent would render nothing to

the user.

connections between these components. The author guides the division by using

visual means, such as the adjacency, colors, patterns, sizes and shapes of the

components. When the image cannot be clearly seen other available information

must be used. For instance, with certain kinds of graphic images the author

can also provide a well-constructed component structure. From that users can

easily discover which graphical elements are included in each component, and

what components are reused in the image.

With some images the rendering order may make it impossible to follow a

logical component structure. In this case the structure needs to be clearly

explained in the

not remove the need for author-provided equivalent information. But it can

help a user to gain deeper understanding of the image. Authoring tools can

support authors to provide a good structure that is easy to understand by

providing ways to visualize the component hierarchy (refer to Authoring Tool

Accessibility Guidelines [ATAG10], checkpoint 3.2).

The reuse of components saves time as users only need to examine the same

component once. The ability to reuse structured components also helps authors,

including authors with disabilities, because changing images becomes easier to

manage. The structure of an image can also help the author when it is used for

editing purposes. This is a requirement of the Authoring Tool Accessibility

Guidelines (refer to to [ATAG10], Checkpoint 7.5).

Because image components can include alternative equivalents, it is also

possible to build up libraries of annotated multimedia (refer to to [ATAG10], Checkpoint 3.5).

circles, ellipses and polygons. Manipulating these shapes is often easier than

drawing in free space (which is why it is a common feature of image authoring

tools), and SVG allows the information that there is a square or an ellipse to

be encoded in the image. This allows easy editing of the shapes as shapes. As

we show in section 4.1 the use of stylesheets can make

it easy to at least list the basic shape or shapes used to represent an

object. In the following example (3.1) we create the basis of the hub for the

network image. We have two rectangles, one inside the other, and a small

circle inside the larger rectangle.

3.2 Reusing Alternative Text as

Images often include text that explains or names the elements presented in

the image. In raster formats the text is converted to pixels and is no longer

available to assistive technologies, but with SVG the text is contained in

text from other elements, such as text equivalents, can be reused. This helps

in managing text as it only needs to be changed at one place.This can help

authors for whom entering content is difficult, and helps by ensuring that

when one piece of text changes other text that depends on it will

automatically be updated..

In the following example (3.3), we add a

image of the Hub that was described in Example 3.1.

This

image by referring to it with a

part of the

to the

easier to understand the structure of complex images as the reusable

components are defined only once and therefore need to be studied and

understood only once. This helps especially if the alternative means of

examining the image are more time consuming. Serial means of inspecting

information (for example speech output or braille) have often been compared to

reading through a soda straw. It can take a lot longer to understand context

and relationships than it does by visual inspection since it is a slower means

of receiving the information, and a mental model of the relationships must

often be assembled without the benefit of a visual representation of the

structure.

An authoring tool may also utilize this feature to help to create and

modify graphics with standard components. This can also help authors who have

difficulties with fine motor control as there is less drawing and writing

required.

In the following example (3.5) we define a socket, and add several of them

to the hub defined earlier:

3.4 Re-Using Components from Other

SVG images can also include components or complete images from other

documents using XML Linking Language [XLINK]. Xlink

enables easy construction and re-use of libraries of known images which can be

available locally or on the Web. For authors, this means being able to use a

known graphic component even when it cannot be seen. For users who cannot see,

a library of described images or image components can be used to help identify

standard graphic components.

The following example (3.7) adds images and symbols from the web, a

earlier.

Note that we did not add

for the

already contains those elements, and has its own Document Object Model (this

would not be the case if the hub had been a raster image format). According to

Checkpoint 2.1 of the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines [UAAG10]] these equivalents should be made available to the

user by a user agent. Similarly each computer image already has a

does not need to be repeated. But each computer needs an individual

separation of structure and information from style and presentation (refer to

[WCAG10], Checkpoint 3.3 and Guideline 3). When the

author separates structure from the description of how it is to be rendered,

users can more easily adapt the rendering to meet their needs. Furthermore, an

author working with a graphic editor can adjust the presentation to suit their

needs for authoring and provide a different presentation for publishing as

required by Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines [ATAG10] Checkpoint 7.2.

Positioning graphic elements is so fundamental to most images that it is

generally included in the SVG elements themselves, but stylesheets can be used

for all other style definitions.

There are some style properties that are unique to SVG such as

extensions for using effects written in SVG, but the syntax is the same.

Importantly, SVG uses the CSS2 [CSS2] version of the

Cascade, providing the user with the final say over presentation.

In the following sections we look at different aspects of separating style

and content in SVG. We start with adding simple style definitions to SVG

elements. We then look at using classes to add more semantics and grouping to

the elements, and providing style definitions for different media. Finally, we

illustrate how SVG allows authors to define their own style effects to be used

for fonts, masks, filters, fills, etc. In this way it is often possible to

prevent the loss of important information that might otherwise be mixed with

style definitions.

with stylesheets. Stylesheets give the author a means to specify rich

presentations, while ensuring that the different presentation-related needs of

users can be met (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoint 3.3 and

Guideline 3 in general and to Accessibility Features of CSS2 [CSS-access]).

Although it is possible to specify style as attributes of particular

elements, or as part of a

demonstrate mostly external linked stylesheets. The User Agent Guidelines [UAAG10] require that a user can select among stylesheets,

including user stylesheets, and with external stylesheets authors can more

easily supply a set of alternative stylesheets. An external stylesheet or a

separate style element helps the author to make style changes to selected

elements in one place.

Style rules using element or class selectors should generally be preferred

over the styles based on

attributes. Classes can be valuable, for instance if the graphical elements or

their combinations have different semantic meanings (see examples in Section

4.2). Inline style attributes or

element's style needs to be changed separately. Although this may be managed

for authors by their authoring tools, inline styles are also more difficult to

override for users with disabilities or with restrictions in their environment

or the devices that they are using. This is especially true if the inline

style definitions illustrate an implicit semantic grouping of the elements

with no

If a particular set of inline style properties is used consistently it can

be a good clue that the set of properties are being used to identify a class

of objects. Instead the objects should have an appropriate

attribute and a stylesheet should be used to provide presentation

information.

In SVG, the default rendering of graphic elements is a black fill, so

without a stylesheet all the presented shapes would be solid black. To avoid

that, the previous examples provide a link to the simple stylesheet presented

in the next example (4.1). It contains simple style definitions for rendering

simple graphic elements like rectangles, circles and paths.

The content of

rendered by default in many circumstances. The following example (4.2) gives a

simple CSS stylesheet that can be used with a structured set of text

alternatives, such as in figure 2.2, to render the

content as text. The stylesheet makes only the

be bigger and bolder than the other titles. The

declaration is used after each definition to make sure that when a user

applies this stylesheet it can override author-supplied style. The result has

been shown in figure 2.3 above.

To give the user a rough idea of the graphics shapes used in an image we

can use the following stylesheet (example 4.3). It will render the types of

common graphics elements as text in between the

some information of the graphical shapes used in the Hub in Examples 3.1 and

3.2.

With CSS alone we cannot describe how the shapes are positioned in respect

of one another, but it is possible to create specialized user agents that can

read the SVG and describe the image in terms of shapes positioned above,

below, inside each other. This information can be very helpful in interpreting

some types of images for particular purposes, for example in describing

construction of simple objects.

to use classes to add semantics that can be used with style definitions. In

the next example we define an image of a computer to be used in the network we

have been building. The stylesheet for this image uses

attributes to define styles for various types of image components. In

particular the class

rendered with minimal graphical details. (We also define a component with a

class of

stylesheet).

The following stylesheet defines some styles for the computer and its

components.

This is beneficial for accessibility as people with disabilities often use

assistive technologies. For instance some media such as screens are suited to

high-resolution graphics, while other media such as braille are better suited

to lower resolution graphics, and some people use audio instead of graphics.

Authors are therefore encouraged to provide a variety of ready-made

stylesheets to cover different user needs (for example audio rendering). CSS

can be used to provide an appropriate default presentation for all these

different devices.

In the following example (4.7) we expand the stylesheet presented in the

last example (4.6) to provide a simplified version of the image for

low-resolution media, such as embossed, braille, handheld, or projection

devices using the

defined in example 4.4. The appropriate set of style

definitions for those devices are selected by using CSS

rules [CSS2]. Within the simplified version only the text

and the outline of graphics components will be rendered, while the screen

media definitions use the default style presented in the previous example

(4.6).

by using assistive technologies. However, authors often want to control the

presentation of the text, for example for branding and visual communication

purposes. In the past this has been done on the Web by providing an image of

the desired text in a raster format. Instead, SVG enables this level of

control by providing support for using already existing fonts or creating new

fonts by using the graphics elements of SVG. This provides authors with a

powerful mechanism for offering new sophisticated and extremely specialized

fonts. At the same time the actual text rendered in those fonts can be

accessed directly by the user agent.

The style definitions are gathered together and referenced through the

classes in the elements instead of using a style attribute. This makes it

easier for a user to override styles for different classes of elements when

necessary. For instance, users with low vision or with color deficiencies

might need to override style properties to read the text.

The following example uses a font named BaseTwelve to create the W3C logo.

If the user does not have the BaseTwelve font then another (in this case

system default) font will be used to render the text. Because the font is

referenced from a CSS style declaration a user can also easily override it. Of

course because this is an XML document a stylesheet can also be used to render

the content (the letters "W 3 C") as a text-based presentation.

4.5 Presentation of Text - Creating

Often a particular font that users are not likely to have will be desired

for a logo. In SVG a new font can be defined by using the

element. The following example defines a font named w3clogofont. It includes

the glyphs for the characters W, 3, and C. Each glyph element has a

human-readable title, and the letter C has a description of the special effect

provided for it.

Note that in the previous code example (4.9), the special shadow effect was

defined with a mask, whereas in the following example (4.10) the character is

defined directly. Authoring tools may choose to use either method for SVG

fonts, depending on performance considerations. However it is important that

the text content is in fact the required text - it would be possible to get

the mask effect by placing a white "C" over the black one, but the text

content would then be "W3CC" which is wrong. Use of SVG fonts allows designers

to create very sophisticated or individual fonts while keeping the content as

text.

to accessibility, the more that authors can easily separate information and

its stylistic presentation the better. SVG supports this separation by

providing a number of features that are defined using SVG elements, but used

as style properties. For instance in the previous two examples (4.9 and 4.10)

we used a mask to create a style effect for a font and then demonstrated an

alternative which can be used as an optimization when creating a custom font.

We can also define patterns, clipping paths and filter effects in SVG and then

use them in a stylesheet. These SVG-based effects cannot be defined in the

stylesheet itself as the definitions require the graphic power of SVG.

In this way the possible range of style effects can be easily extended. At

the same time they can still be clearly separated in parsing and processing

from the information being presented, as required by Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines [WCAG10] Checkpoint 3.3. In the following

example (4.11) we create some stylistic effects for the computer defined in

example 4.4 that are written in SVG but used from a stylesheet in the

rendering process. This means a user can override the effects with another

stylesheet if required, as discussed above. In this example we have defined

gradient effects in a separate document, although it is also possible to

define them within the image that they are first used in. In either case, they

can then be reused in many documents, in the same way as a stylesheet or a

known graphic component, and known patterns can be reused by an author who may

have great difficulty in creating them.

The following example (4.12) is an extended version of the stylesheet

presented in Example 4.7 that uses the gradients to

provide additional style for the computer in Example

4.4.

document regardless of the physical characteristics of the user agent or

assistive technology used. In particular, the User Agent Accessibility

Guidelines [UAAG10] require that the user can activate

all the active elements in a

document. SVG supports the use of the Document Object Model (DOM) and

device-independent events, and they are highly recommended.

SVG also supports declarative definition of animations. These offer users

better means to understand what is being changed and how than the use of

scripting languages, such as Javascript or ECMAscript. For instance, it is

easier to ensure that a user can turn off animations while still being

presented with appropriate content, which is important for accessibility.

Finally, the users should be able to interact with links and other

navigation means embedded in SVG images either serially, by using text

equivalents, or spatially with more visual means.

which supports device-independent interactive content. This allows authors of

SVG to to ensure that interactive content does not rely on a user having a

particular type of device. Good authoring practice will normally use the

rather than the device specific events for gaining and losing the focus on an

element or activating the element. In the next example (5.1) the animation is

triggered by an

different types of activations. Device-independent scripting is required by

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines [WCAG10]

checkpoints 9.3 and 6.4.

An accessible user agent will allow the triggering events to be generated

from a mouse or other pointer device (where available) as well as from a

keyboard. According to the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines [UAAG10], Guideline 1 and especially Checkpoint 1.1, user

agents must provide device-independent ways of activating all application

functions and indicate how those functions are activated (for example a

text-based system could provide a "context menu" listing available actions to

the user).

movement to highlight important points. But animation may also prevent users

from reading adjacent information in the page, and animations with a certain

refresh rate can trigger discomfort or seizures in users with photosensitive

epilepsy. Users may also have difficulties in making selections fast enough if

they are embedded in the animation. Therefore animations need to be designed

carefully so that they do not affect accessibility or usability of the

presentation. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines require that until user

agents allow the user to freeze or control the rate of an animation authors

should ensure that users can pause or stop moving content (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoint, 3.5, 3.6, 3.8 and 7.3, and Guidelines

3 and 7), and the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines require that the

necessary functionality is provided by user agents (refer to [UAAG10] Checkpoints 1.1, 7.3 and Guideline 5) Note that it

is primarily a user agent rather than an authoring responsibility to provide

this functionality. SVG also provides means, such as the

element, to control the rendering of images containing animation for static

media such as print-output devices. We discuss

The animation model in SVG has been jointly developed by the SVG and the

Synchronized Multimedia (SYMM) working groups, and is based

on the SMIL-Boston animation specification [SMIL-animation]. The model offers a declarative

approach for creating dynamic Web content. In many cases, this is simpler to

understand and use than the programmatic model used in scripting languages

such as ECMAscript or Javascript, when a non-graphic presentation is required.

The animation model aims to allow user agents to provide information about

what an animation is supposed to do even when the rendering device or

environment does not have the media capabilities presumed by the author.

Because SVG is XML it provides user agents with a Document Object Model

(DOM), as discussed in Section 7 below. The

directly accessible to User Agents. As the animation effects do not produce

any changes in the DOM, the presentation related to animations can be handled

separately. A non-visual user agent can interpret the declarative description

of the animation and render it in the most appropriate manner. The User Agent

Accessibility guidelines require that a user agent provide assistive

technology with access to the DOM (refer to [UAAG10],

Checkpoints 5.1, 5.4 and Guideline 5 in general), so assistive technologies

can also provide an appropriate presentation of the animation effect when used

in conjunction with an SVG browser.

In the following example we use animation to highlight the path of messages

from Computer A to the outside world, or between computer A and computer B.

For some components we are animating style properties of the components. But

for some we also want to update the text equivalents, so we define two symbols

with different

and the animation effect swaps between them.

by including the graphics component inside an

that explains the target of the link and appropriate

linked to the target. The textual explanations are very important for the

users with blindness or low vision as they often navigate through the document

by moving from link to link and reading the link text or its text equivalent.

It is therefore important that the link (and its text equivalent) make sense

on its own (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoint 13.3). Unless

SVG User Agents make this textual information available, authors will need to

include text-based links to content as well (refer to [WCAG10] checkpoint 1.5, although this should not apply to

newer user agents such as those designed for SVG).

Users relying heavily on visual information, such as some users with

cognitive disabilities, may also need graphical links to be easily identified

by visual means. For graphical links there is no default highlighting

convention as underline is for textual links. These may be highlighted by

expanding the size or color of the linked component, or adding a graphic mark

near the component. We may also highlight the component only when it gets

focus or when the user asks to see the links. Authors and user agents should

aim for consistency when offering default highlighting styles. It is also

important that users can easily change the highlighting according to their

needs. This can be provided in user agents by implementing the relevant

stylesheet features, for example in CSS [CSS2].

As many users who cannot use a pointing device navigate through links in

serial order they need to be able to create a good mental model of the

structures and shortcuts that make navigation more effective (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoints 13.4, 13.5, and Guideline 3 in

general). Such users will benefit if links can be traversed in an order that

corresponds to the graphic structure, or if links related to a certain

structure (for example all the buttons included in a cockpit radio panel) are

grouped and can be easily skipped (refer to [WCAG10],

Checkpoint 13.6).

6. Adapting Content to User or System

It is possible in SVG to provide alternatives based on whether a feature is

supported (for example animation). This is done with the

element using

attributes. The following example (6.1) extends the previous animated example

(5.1). It uses the

supports animation, and if not provides an alternative explanation of how the

network passes messages. The

used instead (or as well) to provide multiple versions of text according to

the language, or to provide a sign-language version of descriptive text.

7. Accessibility Benefits from

All markup languages written in XML automatically have some accessibility

benefits. This is true also with SVG. In this section we explain how these

features of XML can be used to increase the accessibility of SVG

documents.

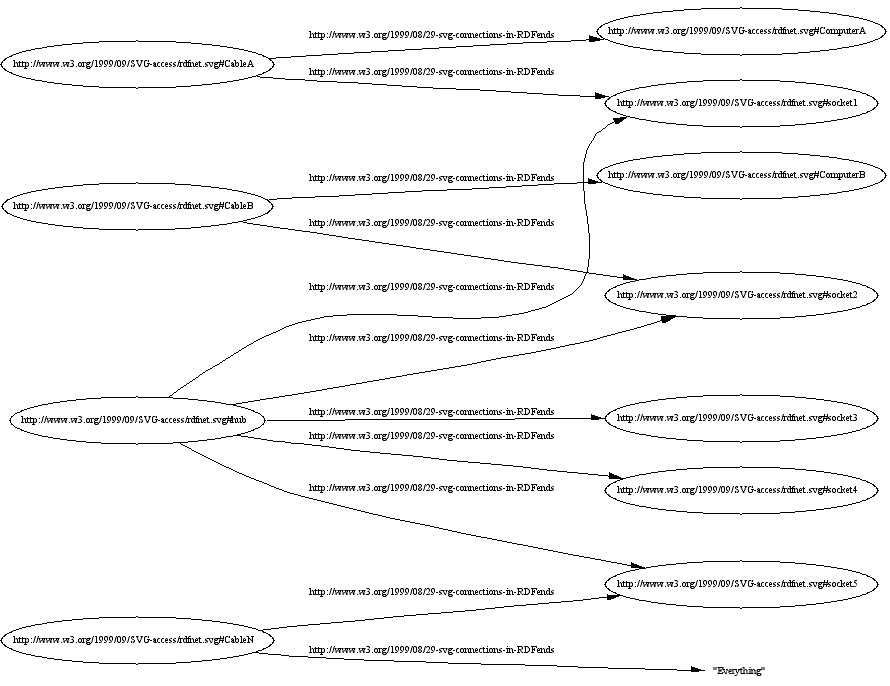

7.1 Providing Information with

The more information the author can provide about an SVG image and its

components the better it is for accessibility. Adding metadata to a document

can help the user search for information, for example documents with a

suitable accessibility rating. In the following example we have used it to

describe the image further - although reading the XML structure shows that the

network consists of a hub, some cables and some computers, it does not explain

which are connected to which. We have included an automatically generated

image of the relationships described by the metadata - the same information

can be generated by an assistive technology. Combining the information with

the equivalent alternatives included in the image can be used to provide a

navigable, described network in text, audio, or even using substituted icons (

[WCAG10] Checkpoint 13.2 requires metadata, 14.2

requires illustration of information and Guideline 1 requires text

equivalents). The following example (7.1) uses XML namespaces [NAMESPACE] and the Resource Description Framework [RDF] to add some metadata about the cables connecting the

computers and the hub in the earlier network image.

7.2 Using SVG with Other XML

The SVG specification allows the use of XML namespaces [NAMESPACE] to introduce elements from other XML

languages. In particular, the

using extensions to the SVG DTD or using another namespace. In the following

example we include some SMIL [SMIL] to provide richer

descriptions of the image in Figure 5.1 (the example assumes that a stylesheet

provides positioning for the textstream).

7.3 Supporting Assistive Technologies - Document

SVG supports a Document Object Model [DOM2] which

provides a standard interface (Application Programming Interface or

API) to examine and manipulate document structure. It can be used

by various tools and technologies. DOM is particularly beneficial to assistive

technologies as they are often used in conjunction with "standard" tools such

as common user agents. For example, a screen reader which provides voice

output from a variety of applications can be customized to take advantage of

the DOM interface. This can provide better access than would be possible if it

were relying entirely on the standard rendering engine (perhaps a graphics

editor, or a browser plug-in) for getting the data. An assistive technology

can also use the DOM interface to change an SVG image to suit the needs of a

user. Note that the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines require that user

agents implement the DOM and export interfaces to assistive technologies

(refer to [UAAG10], Checkpoint 1.3, and Guidelines 1 and

5). See also section 5.2 on accessible events -

these are inherited from the DOM 2 specification [DOM2].

conformance to accessibility guidelines as part of conformance for tools. See

in particular the appendix on accessibility. In addition, the public Web page

of the W3C SVG working group [SVG-page] is a good

source of information, including articles and papers about SVG, news of

implementations, etc.

About the Web Accessibility

W3C's Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) addresses accessibility of the Web

through five complementary activities that:

disability organizations, accessibility research organizations, and

governments interested in creating an accessible Web. WAI sponsors include the

US National Science Foundation and Department of Education's National

Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research; the European Commission's

DG XIII Telematics Applications Programme for Disabled and Elderly; Government

of Canada, Industry Canada; IBM, Lotus Development Corporation, Microsoft, and

Verizon. Additional information on WAI is available at http://www.w3.org/WAI.

About the World Wide Web Consortium

The W3C was created to lead the Web to its full potential by developing

common protocols that promote its evolution and ensure its interoperability.

It is an international industry consortium jointly run by the Laboratory for

Computer Science (LCS) at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the

USA, the National Institute for Research in Computer Science and Control

(INRIA) in France and Keio University in Japan. Services provided by the

Consortium include: a repository of information about the World Wide Web for

developers and users; reference code implementations to embody and promote

standards; and various prototype and sample applications to demonstrate use of

new technology. In July 2000, 433 organizations are Members of the Consortium.

For more information about the World Wide Web Consortium, see http://www.w3.org/.

10.

We would like to thank the following people who have contributed

substantially to this document:

Judy Brewer, Dan Brickley, Daniel Dardailler, Jon Ferraiolo, Ian Jacobs,

Chris Lilley, Eric Prud'hommeaux, Ralph Swick, Dave Woolley, the SVG Working Group and the WAI

Protocols and Formats Working Group.

Accessibility Features of SVG

W3C Note 7 August

2000

- This version:

- http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/NOTE-SVG-access-20000807

- (Also available for download as a gzipped tarball, or in zip format)

- Latest version:

- http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG-access

- Editors:

- Charles McCathieNevile <charles@w3.org>

Marja-Riitta Koivunen <marja@w3.org>

Copyright © 1999-2000 W3C® (MIT, INRIA,

Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C

liability,

trademark, document

use and software

licensing rules apply.

Abstract

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) offers a number offeatures to make graphics on the Web more accessible than is currently

possible, to a wider group of users. Users who benefit include users with low

vision, color blind or blind users, and users of assistive technologies. A

number of these SVG features can also increase usability of content for many

users without disabilities, such as users of personal digital assistants,

mobile phones or other non-traditional Web access devices.

Accessibility requires that the features offered by SVG are correctly used

and supported. This Note describes the SVG features that support accessibility

and illustrates their use with examples.

Status of this document

This document is a Note made available by the W3C for discussion only.Publication of this Note by W3C indicates no endorsement by the W3C

Team or any W3C Members. The Note is based on the

SVG Candidate Recommendation [SVG].

This Note is made available at the same time as the SVG

Candidate Recommendation in order to provide

information on potential implementation considerations.

This version of the Note has received some review but not yet endorsement

from the SVG Working Group and the Protocols and Formats Working Group. These

groups, together with the Education and Outreach Working Group, the WAI

Interest Group, and others are invited to review this document,

in particular, during the SVG Candidate Recommendation period.

The authors plan to publish an updated version of this Note in any of the

following circumstances:

- Further review, especially by W3C Working or Interest Groups, indicates

that change is needed. - Significant changes are made to the SVG specification.

- SVG becomes a W3C Recommendation.

mailing list w3c-wai-eo@w3.org, which

is archived

publicly at http://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/w3c-wai-eo/. This document

has been produced as part of the WAI

Technical Activity. A list of current W3C technical reports

and publications, including Working Drafts and Notes, can be found at

http://www.w3.org/TR.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Equivalent Alternatives

- Accessible Graphics

- Controlling Presentation

- Accessible Interaction

- Adapting Content to User or System Settings

- Accessibility Benefits Originating from XML

- Further Reading

- Glossary

- Acknowledgements

- References

1. Introduction

1.1 Why Accessibility?

Images, sound, text and interaction all play a role in conveyinginformation on the Web. In many cases, images have an important role in

conveying, clarifying, and simplifying information. In this way, multimedia

itself benefits accessibility. However the information presented in images

must be accessible to all users, including users with non-visual devices.

Furthermore, in order to have full access to the Web, it is important that

authors with disabilities can create Web content, including images as part of

that content.

The working context of people with (or without) disabilities can vary

enormously. Many users or authors:

- may not be able to see the images at all or may have impaired vision or

hearing; - may have difficulty reading or comprehending text;

- may not be able to move easily or use a keyboard or mouse when creating

or interacting with the image; - may use a device with a text-only display, or a small or very magnified

screen view.

and authors including many people who do not have a disability but who have

similar needs. For example, someone may be working in an eyes-busy environment

and thus may require an audio equivalent for information they cannot view.

Users of small mobile devices (with small screens, no keyboard, and no mouse)

have similar functional needs to users with certain disabilities. For some

further information on how people with disabilities use the Web, refer to "How

People with Disabilities Use the Web" [USENOTE].

1.2 Accessible SVG?

Scalable Vector Graphics [SVG] is an Extensible MarkupLanguage (XML) application for producing Web graphics. SVG

provides many accessibility benefits to disabled users, some originating from

the vector graphics model, some inherited because SVG is built on top of XML,

and some in the design of SVG itself, for example, SVG-specific elements for

alternative equivalents.

SVG images are scalable - they can be zoomed and resized by the reader as

needed. Scaling can help users with low vision and users of some assistive

technologies (e.g., tactile graphic devices, which typically have a very low

resolution).

The following example illustrates the scalability of a vector graphics

image. The first row shows a small PNG and a corresponding

SVG image, which look the same. The second row shows an enlargement of both.

The enlarged PNG version of the image has suffered a significant loss of

quality, while the enlarged SVG version looks smooth and shows more details

than before. Scalable graphics can help users with low vision make sense of an

image at a size that best suits their needs.

Small PNG image: |

Small SVG image: |

Enlarged PNG image: |

Enlarged SVG image: |

Structured images

The most common way authors make a raster image (e.g.,GIF or PNG images) accessible on the Web is to

provide a text equivalent that may be rendered with or without the image.

Often, this text equivalent is the only information available for non-visual

rendering, as the raster image is stored as a matrix of colored dots,

generally with no structural information. Structural information can be added

to any image as metadata, but managing it separately from the visible image is

tedious, making it less likely that authors will create and use it with

careful attention. SVG's

vector-graphics format stores structural information about graphical shapes as

an integral part of the image. As we discuss below, this information can be

used by assistive technologies to increase accessibility, especially when this

structural information is complemented by alternative equivalents and

metadata.

Alternative equivalents

In addition to image structure, SVG allows for alternative equivalents - content that users can accessto help them understand the image. In particular, SVG authors to include a

text description for each logical component of an image, and a text title to

explain the component's role in the image as a whole. Text is considered very

accessible to users with a range of disabilities (e.g., some vision

impairments and some cognitive disabilities) since it may be rendered on

screen, as speech, or as Braille using readily available assistive technology.

XML - Plain text

One major accessibility benefit derived from XML is that an SVG image isencoded as plain text. Authors can create and edit it with a text-processor or

XML authoring tool (there are other properties of SVG that make this easier

than it might seem at first). A number of popular Web design tools are in fact

enhanced text-editing applications, and for users with certain types of

disabilities, these are much easier to use. Naturally, it is also possible to

use graphic SVG authoring tools that require very little reading and writing,

which helps people with other types of disabilities.

Plain text encoding also means that people may use relatively simple,

text-based XML user agents to render SVG as text, braille, or audio. This can

help users with visual impairments, and can be used to supplement graphical

rendering.

XML - Stylesheets

The separation of style from the rest of the content is very important foraccessibility. Authors may use CSS or XSL style sheets to control the

rendering of SVG images, a feature common to all markup languages written in

XML. Users who might otherwise be unable to access content can define

stylesheets to control the rendering of SVG images, meeting their needs

without losing additional author-supplied style.

Extended Styling

SVG offers a number of style features beyond the properties defined in CSSto provide specific graphic effects for controlling how images are rendered.

These style features can help authors to create content that can be easily

adapted to the needs of users with low vision, color deficiencies, or users

with assistive technologies. Features such as masking, filters, and the

ability to define highly sophisticated fonts are all available in SVG.

XML - DOM interface

Another benefit of using XML is that interaction can be made accessiblethrough the Document Object Model (DOM). The DOM interface

can enable the use of many assistive

technologies with SVG images. SVG allows access to both stylesheet and XML

content as it uses DOM version 2 (DOM2) [DOM2].

XML - SVG with other XML languages

SVG documents may be included in documents written in other XML languages,and may also include markup from other XML languages. Mixing markup language

can increase accessibility because authors may use the markup language most

suited to each part of a document (refer to the Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines 1.0 [WCAG10], Guideline 3). For instance, a

MathML document could use SVG for both laying out equations and drawing graphs

of those equations. In examples below, we show how to describe SVG components

and their relationships by embedding RDF metadata and SMIL markup in the

SVG.

1.3 How to read this document

This document highlights the features in SVG that support accessibility. InSections 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 we discuss the accessibility features of SVG

(including the use of stylesheets). Section 7 explains the accessibility

benefits that originate from XML.

This document makes extensive reference to the accessibility requirements

specified in the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 Recommendation

(ATAG10) [ATAG10], the Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 Recommendation (WCAG10) [WCAG10], and the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines

Working Draft (UAAG10) [UAAG10]. It

also makes extensive reference to Cascading Style Sheets Level 2

(CSS2) [CSS2]. A reader who has a basic

knowledge of HTML or XML and of CSS (level one or two) should be able to

understand enough of the markup to make sense of the examples. Even without

that knowledge, it is worth reading the examples to see how they work - as

well as illustrating accessible design in many cases they demonstrate good

general design practices.

To illustrate how to create accessible SVG graphics, we design an SVG

diagram of a computer network, built up from example to example. Examples use

strong emphasis to highlight changes from example to example,

or important features of an example.

2. Equivalent Alternatives

Providing an alternative equivalent for inaccessible content is one of theprimary ways authors can make their documents accessible to people with

disabilities. The alternative content fulfills essentially the same function

or purpose for users with disabilities as the primary content does for users

without any disability. Text equivalents are always required for graphic

information (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoint 1.1, and

Guideline 1 in general). In SVG, providing a hierarchy of text equivalents can

also convey the hierarchical structure of the graphic components. This Note

describes a number of ways to include and use equivalent alternatives.

2.1 Title and Description

The simplest way to specify a text equivalent for an SVG graphic is toinclude the following elements in any SVG container or graphics element:

title- Provides a human-readable title for the element that contains it. The

titleelement may be rendered by a graphical user agent as a tooltip. It may be rendered as speech by a speech synthesizer. desc- Provides a longer more complete description of an element that contains it. Authors should provide descriptions for complex or other content that has functional meaning.

and a description for an image of a computer network. The graphic components

that can actually be drawn will be added to the image in later sections.

<?xml version="1.0"?><!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 20000802//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/DTD/svg-20000802.dtd"> <svg width="6in" height="4.5in" viewBox="0 0 600 450"> <title>Network</title> <desc>An example of a computer network based on a hub</desc> </svg>

2.2 Equivalent Alternatives in a Structured Document

An SVG image may consist of several components combined hierarchically,each of which may have a title and a description. The combination of the

hierarchy and alternative equivalents can help a user who cannot see to create

a rough mental model of an image. SVG authors should therefore build the

hierarchy so that it reflects the components of the object illustrated by the

image. Some guidance for using structure can be found in WCAG10 (refer to [WCAG10], Guidelines 3 and 12).

The component hierarchy with alternative equivalents can be used in

different ways by different user agents. For instance, a simple non-visual

user agent can provide access to the component hierarchy and allow the user to

navigate up and down or at a certain level of the structure, giving the

equivalent description of each encountered component (refer to UAAG10 [UAAG10], Checkpoints 7.6 and 7.7 and Guidelines 7 and 8). A

standard XML browser, which does not render SVG as graphics, may also do this.

A multimedia-capable user agent might name each component that has focus

through speech output, much as some Web browsers render alternative text for

images as tooltips.

The following example (2.2) extends the network image component introduced

in example 2.1 by introducing six subcomponents:

- Hub

- Computer A

- Computer B

- Cable A

- Cable B

- Cable N

g) withan

id attribute and a text equivalent, specified withtitle and desc elements.Example

2.2: A structured SVG document with alternative equivalents (download structure in 2.2).

2.2: A structured SVG document with alternative equivalents (download structure in 2.2).

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 20000802//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/DTD/svg-20000802.dtd">

<svg width="6in" height="4.5in" viewBox="0 0 600 450">

<title>Network</title>

<desc>An example of a computer network based on a hub</desc>

<!-- add graphic content here, and so on for the other components-->

</g>

<g id="ComputerA">

<title>Computer A</title>

<desc>A common desktop PC</desc>

</g>

<g id="ComputerB">

<title>Computer B</title>

<desc>A common desktop PC</desc>

</g>

<g id="CableA">

<title>Cable A</title>

<desc>10BaseT twisted pair cable</desc>

</g>

<g id="CableB">

<title>Cable B</title>

<desc>10BaseT twisted pair cable</desc>

</g>

<g id="CableN">

<title>Cable N</title>

<desc>10BaseT twisted pair cable</desc>

</g>

</svg>show the alternative equivalents as text, as in the next figure (2.3). Example 4.2 in Section 4 shows how to

attach CSS2 [CSS2] style information to the

title and desc elements of the image. Note thatwithout definitions for these elements, a user agent would render nothing to

the user.

Figure

2.3: Textual representation of Example 2.2 when it is rendered

with the stylesheet in Example 4.2.

2.3: Textual representation of Example 2.2 when it is rendered

with the stylesheet in Example 4.2.

Network An example of a computer network

based on a hub

Hub A typical 10baseT/100BaseTX network hub

Computer A A common desktop PC

Computer B A common desktop PC

Cable A 10BaseT twisted pair cable

Cable B 10BaseT twisted pair cable

Cable N 10BaseT twisted pair cable

based on a hub

Hub A typical 10baseT/100BaseTX network hub

Computer A A common desktop PC

Computer B A common desktop PC

Cable A 10BaseT twisted pair cable

Cable B 10BaseT twisted pair cable

Cable N 10BaseT twisted pair cable

3. Accessible Graphics

Users examining images visually can divide them into components andconnections between these components. The author guides the division by using

visual means, such as the adjacency, colors, patterns, sizes and shapes of the

components. When the image cannot be clearly seen other available information

must be used. For instance, with certain kinds of graphic images the author

can also provide a well-constructed component structure. From that users can

easily discover which graphical elements are included in each component, and

what components are reused in the image.

With some images the rendering order may make it impossible to follow a

logical component structure. In this case the structure needs to be clearly

explained in the

desc element. The structural information doesnot remove the need for author-provided equivalent information. But it can

help a user to gain deeper understanding of the image. Authoring tools can

support authors to provide a good structure that is easy to understand by

providing ways to visualize the component hierarchy (refer to Authoring Tool

Accessibility Guidelines [ATAG10], checkpoint 3.2).

The reuse of components saves time as users only need to examine the same

component once. The ability to reuse structured components also helps authors,

including authors with disabilities, because changing images becomes easier to

manage. The structure of an image can also help the author when it is used for

editing purposes. This is a requirement of the Authoring Tool Accessibility

Guidelines (refer to to [ATAG10], Checkpoint 7.5).

Because image components can include alternative equivalents, it is also

possible to build up libraries of annotated multimedia (refer to to [ATAG10], Checkpoint 3.5).

3.1 Basic Graphic Shapes

SVG allows authors to create familiar basic shapes such as rectangles,circles, ellipses and polygons. Manipulating these shapes is often easier than

drawing in free space (which is why it is a common feature of image authoring

tools), and SVG allows the information that there is a square or an ellipse to

be encoded in the image. This allows easy editing of the shapes as shapes. As

we show in section 4.1 the use of stylesheets can make

it easy to at least list the basic shape or shapes used to represent an

object. In the following example (3.1) we create the basis of the hub for the

network image. We have two rectangles, one inside the other, and a small

circle inside the larger rectangle.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="svg-basic-style.css" type="text/css"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 20000802//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/DTD/svg-20000802.dtd">

<svg width="6in" height="4.5in" viewBox="0 0 600 450">

<g transform="translate(10 10)">

<title>Hub</title>

<desc>A typical 10BaseT/100BaseTX network hub</desc>

<rect width="253" height="84"/>

<rect width="230" height="44" x="12" y="10"/>

<circle cx="227" cy="71" r="7"/>

</g>

</svg>Figure 3.2: Visual rendering of Example

3.1.

3.1.

3.2 Reusing Alternative Text as

Graphics

Images often include text that explains or names the elements presented inthe image. In raster formats the text is converted to pixels and is no longer

available to assistive technologies, but with SVG the text is contained in

text elements that keep the textual form intact. Furthermore, thetext from other elements, such as text equivalents, can be reused. This helps

in managing text as it only needs to be changed at one place.This can help

authors for whom entering content is difficult, and helps by ensuring that

when one piece of text changes other text that depends on it will

automatically be updated..

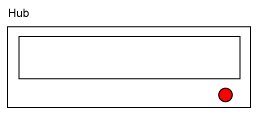

In the following example (3.3), we add a

text element to theimage of the Hub that was described in Example 3.1.

This

text element reuses the title text of the Hubimage by referring to it with a

tref element and rendering it aspart of the

text element. An id attribute is addedto the

title element so that it can be referenced.<?xml version="1.0"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="svg-basic-style.css" type="text/css"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 20000802//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/DTD/svg-20000802.dtd">

<svg width="6in" height="4.5in" viewBox="0 0 600 450">

<g transform="translate(10 30)">

<title id="hub">Hub</title>

<desc>A typical 10BaseT/100BaseTX network hub</desc>

<!-- Re-use the text in the title element -->

<text x="0" y="-10">

<tref xlink:href="#hub"/>

</text>

<rect width="253" height="84"/>

<rect width="230" height="44" x="12" y="10"/>

<circle cx="227" cy="71" r="7"/>

</g>

</svg>Figure 3.4: Visual rendering of Example

3.3.

3.3.

3.3 Reusing Graphic Components

SVG allows the construction and reuse of graphic components. This makes iteasier to understand the structure of complex images as the reusable

components are defined only once and therefore need to be studied and

understood only once. This helps especially if the alternative means of

examining the image are more time consuming. Serial means of inspecting

information (for example speech output or braille) have often been compared to

reading through a soda straw. It can take a lot longer to understand context

and relationships than it does by visual inspection since it is a slower means

of receiving the information, and a mental model of the relationships must

often be assembled without the benefit of a visual representation of the

structure.

An authoring tool may also utilize this feature to help to create and

modify graphics with standard components. This can also help authors who have

difficulties with fine motor control as there is less drawing and writing

required.

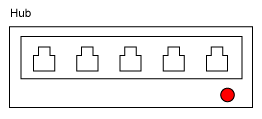

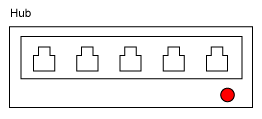

In the following example (3.5) we define a socket, and add several of them

to the hub defined earlier:

Example 3.5: Adding sockets to the Hub in Example 3.3 (download hub image in

3.5).

3.5).

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="svg-basic-style.css" type="text/css"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 20000802//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/DTD/svg-20000802.dtd">

<svg width="6in" height="4.5in" viewBox="0 0 600 450">

<g transform="translate(10 30)">

<!-- Define a socket -->

<defs>

<symbol id="hubPlug">

<desc>A 10BaseT/100baseTX socket</desc>

<path d="M0,5 h5 v-9 h12 v9 h5 v16 h-22 z"/>

</symbol>

</defs>

<title id="hub">Hub</title>

<desc>A typical 10BaseT/100BaseTX network hub</desc>

<text x="0" y="-10">

<tref xlink:href="#hub"/>

</text>

<rect width="253" height="84"/>

<rect width="229" height="44" x="12" y="10"/>

<circle cx="227" cy="71" r="7"/>

<!-- five groups each using the defined socket -->

<g transform="translate(25 25)" id="sock1">

<title>Socket 1</title>

<use xlink:href="#hubPlug"/>

</g>

<g transform="translate(70 25)" id="sock2">

<title>Socket 2</title>

<use xlink:href="#hubPlug"/>

</g>

<!-- (and three more) -->

</g>

</svg>Figure 3.6: A visual rendering of Example

3.5.

3.5.

3.4 Re-Using Components from Other

Documents

SVG images can also include components or complete images from otherdocuments using XML Linking Language [XLINK]. Xlink

enables easy construction and re-use of libraries of known images which can be

available locally or on the Web. For authors, this means being able to use a

known graphic component even when it cannot be seen. For users who cannot see,

a library of described images or image components can be used to help identify

standard graphic components.

The following example (3.7) adds images and symbols from the web, a

text element and some graphics to the Network structure presentedearlier.

Example 3.7: Adding graphics to the Network

components presented in Example 2.2 (download network image in 3.7).

components presented in Example 2.2 (download network image in 3.7).

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="svg-style.css" type="text/css"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 20000802//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/DTD/svg-20000802.dtd">

<svg width="6in" height="4.5in" viewBox="0 0 600 450">

<title id="mainTitle">Network</title>

<desc>An example of a computer network based on a hub</desc>

<!-- Draw text. -->

<text x="0" y="-10">

<tref xlink:href="#mainTitle"/>

</text>

<!-- Use the hub image and its title and description information. -->

<g id="hub" transform="translate(180 200)">

<image width="600" height="450" xlink:href="hub.svg"/>

</g>

<!-- Use an external computer symbol. Scale to fit. -->

<g id="ComputerA" transform="translate(20 170)">

<title>Computer A</title>

<use xlink:href="computer.svg#terminal"

transform="scale(0.5)"/>

</g>

<!-- Use the same computer symbol. -->

<g id="ComputerB" transform="translate(300 170)">

<title>Computer B</title>

<use xlink:href="computer.svg#terminal"

transform="scale(0.5)"/>

</g>

<g id="CableA" transform="translate(107 88)">

<title>Cable A</title>

<desc>10BaseT twisted pair cable</desc>

<!-- Draw Cable A. -->

<path d="M0,0c100,140 50,140 -8,160"/>

</g>

<!-- (and the other two cables) -->

</svg>title or desc elementsfor the

hub component, since it refers to an SVG image thatalready contains those elements, and has its own Document Object Model (this

would not be the case if the hub had been a raster image format). According to

Checkpoint 2.1 of the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines [UAAG10]] these equivalents should be made available to the

user by a user agent. Similarly each computer image already has a

descsymbol element so itdoes not need to be repeated. But each computer needs an individual

title to describe the role it plays in the network image.Figure 3.8: A visual rendering of Example 3.7.

4. Controlling Presentation

One of the main themes in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines is theseparation of structure and information from style and presentation (refer to

[WCAG10], Checkpoint 3.3 and Guideline 3). When the

author separates structure from the description of how it is to be rendered,

users can more easily adapt the rendering to meet their needs. Furthermore, an

author working with a graphic editor can adjust the presentation to suit their

needs for authoring and provide a different presentation for publishing as

required by Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines [ATAG10] Checkpoint 7.2.

Positioning graphic elements is so fundamental to most images that it is

generally included in the SVG elements themselves, but stylesheets can be used

for all other style definitions.

There are some style properties that are unique to SVG such as

fill, stroke and stroke-width, and theextensions for using effects written in SVG, but the syntax is the same.

Importantly, SVG uses the CSS2 [CSS2] version of the

Cascade, providing the user with the final say over presentation.

In the following sections we look at different aspects of separating style

and content in SVG. We start with adding simple style definitions to SVG

elements. We then look at using classes to add more semantics and grouping to

the elements, and providing style definitions for different media. Finally, we

illustrate how SVG allows authors to define their own style effects to be used

for fonts, masks, filters, fills, etc. In this way it is often possible to

prevent the loss of important information that might otherwise be mixed with

style definitions.

4.1 Simple Style Definitions

SVG uses CSS syntax and properties or XSL to specify formatting effectswith stylesheets. Stylesheets give the author a means to specify rich

presentations, while ensuring that the different presentation-related needs of

users can be met (refer to [WCAG10], Checkpoint 3.3 and

Guideline 3 in general and to Accessibility Features of CSS2 [CSS-access]).

Although it is possible to specify style as attributes of particular

elements, or as part of a

style element, we have chosen todemonstrate mostly external linked stylesheets. The User Agent Guidelines [UAAG10] require that a user can select among stylesheets,

including user stylesheets, and with external stylesheets authors can more

easily supply a set of alternative stylesheets. An external stylesheet or a

separate style element helps the author to make style changes to selected

elements in one place.

Style rules using element or class selectors should generally be preferred

over the styles based on

id attribute selectors or inline styleattributes. Classes can be valuable, for instance if the graphical elements or

their combinations have different semantic meanings (see examples in Section

4.2). Inline style attributes or

id-based style rules mean eachelement's style needs to be changed separately. Although this may be managed

for authors by their authoring tools, inline styles are also more difficult to

override for users with disabilities or with restrictions in their environment

or the devices that they are using. This is especially true if the inline

style definitions illustrate an implicit semantic grouping of the elements

with no

class definitions to support it.If a particular set of inline style properties is used consistently it can

be a good clue that the set of properties are being used to identify a class

of objects. Instead the objects should have an appropriate

classattribute and a stylesheet should be used to provide presentation

information.

In SVG, the default rendering of graphic elements is a black fill, so

without a stylesheet all the presented shapes would be solid black. To avoid

that, the previous examples provide a link to the simple stylesheet presented

in the next example (4.1). It contains simple style definitions for rendering

simple graphic elements like rectangles, circles and paths.

Example 4.1: A simple stylesheet for

presenting rectangle, circle, and path elements (download stylesheet in 4.1).

presenting rectangle, circle, and path elements (download stylesheet in 4.1).

rect { fill: white; stroke: black;

stroke-width: 1

}

circle { fill: red; stroke: black;

stroke-width: 1

}

path { fill: white; stroke: black;

stroke-width: 1

}title and desc elements may not berendered by default in many circumstances. The following example (4.2) gives a

simple CSS stylesheet that can be used with a structured set of text

alternatives, such as in figure 2.2, to render the

content as text. The stylesheet makes only the

title anddesc elements visible, as a block. Furthermore, thetitle element directly inside the svg element willbe bigger and bolder than the other titles. The

!importantdeclaration is used after each definition to make sure that when a user

applies this stylesheet it can override author-supplied style. The result has

been shown in figure 2.3 above.

Example 4.2: A simple

stylesheet to present

text (download stylesheet in 4.2).

stylesheet to present

title and desc elements astext (download stylesheet in 4.2).

svg { visibility: hidden !important }

title { visibility: visible !important }

desc { visibility: visible !important }

g { display: block !important }

svg > title {

font-size: 120% !important;

font-weight: bolder !important

}can use the following stylesheet (example 4.3). It will render the types of

common graphics elements as text in between the

title anddesc renderings. We can use the stylesheet, for instance, to givesome information of the graphical shapes used in the Hub in Examples 3.1 and

3.2.

With CSS alone we cannot describe how the shapes are positioned in respect

of one another, but it is possible to create specialized user agents that can

read the SVG and describe the image in terms of shapes positioned above,

below, inside each other. This information can be very helpful in interpreting

some types of images for particular purposes, for example in describing

construction of simple objects.

Example 4.3: A simple stylesheet with text

for graphical shapes (download stylesheet in

4.3).

for graphical shapes (download stylesheet in

4.3).

svg { visibility: hidden !important }

title { visibility: visible !important }

desc { visibility: visible !important }

g { display: block !important }

svg > title {

font-size: 120% !important;

font-weight: bolder !important;

}

rect:before {

visibility: visible;

content: "rectangle " !important

}

ellipse:before {

visibility: visible;

content: "ellipse " !important

}

circle:before {

visibility: visible;

content: "circle " !important

}

path[d ~= z]:before,

polygon:before {

visibility: visible;

content: "closed shape " !important

}4.2 Style Definitions with Classes

As discussed earlier, with graphic images it is often necessary or helpfulto use classes to add semantics that can be used with style definitions. In